US Debt: Volatility Could Queitly Erode "Exorbitant Privilege"

U.S. debt hinges more on steady investor appetite than on repayment capacity; persistent rate volatility could chip away at even the strong structural demand for Treasuries.

I started pulling together the data a couple of days ago, and —right on cue— as I pen down the words today, the long end is melting down on my screen. Talk about timely research…

TL;DR

Ratings vs. Reality: Moody’s downgrade barely moved equities, but Treasuries sold off — reminding us that yields, not letter grades, ultimately decide debt sustainability.

Ability to Pay ≠ Willingness to Fund: The U.S. can always print dollars, so default risk is trivial; the real risk is that investors demand a higher risk premium if Washington looks cavalier about rising interest costs and fiscal discipline.

Two Pillars of “Exorbitant Privilege” are Holding Together Dollar Demand:

By choice — reserve managers, insurers, pensions, and corporates buy Treasuries for safety, liquidity, and benchmark status.

By force — lack of true alternatives, cap-weighted bond indices, 60/40 portfolio constructions in a world of US equities dominance automatically channel global savings back into Treasuries.

Volatility Is the Silent Threat: Historical data show that when long-bond volatility spikes, central-bank reserve managers quietly trim USD allocations. The danger is not a sudden exodus, but incremental re-weighting that pushes yields up just when supply is already surging.

For the US, Ratings Don’t Rate

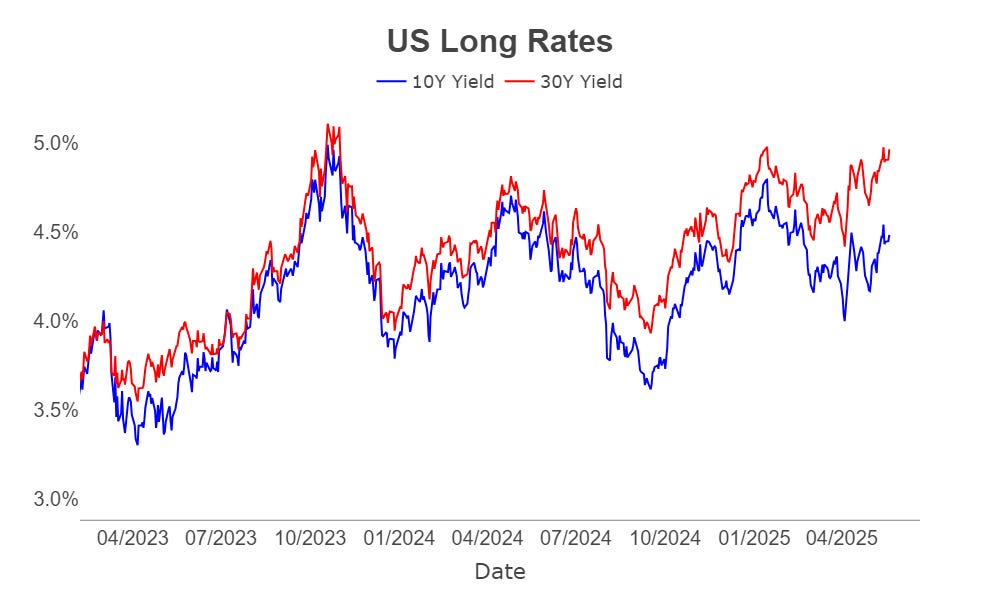

Moody’s downgrade produced a fleeting wobble in risk assets. S&P futures slipped overnight and were back in the green by the next U.S. open. The Treasury market, in contrast, saw 10-year yields lurch toward 5 percent. That is the venue where fiscal concerns price in — and the venue that matters for taxpayers and investors alike.

My favorite doomsayer Ray Dalio recently pointed out that we shouldn’t take sovereign credit ratings at face value, as they don’t consider the risk of the central bank inflating its debt away. On technicality, that is not really accurate. Moody’s - or any other rating agency - does consider institutional factors when rating a country. An Aa1 rating implies that they still trust the Fed won’t morph into the monetary arm of the Treasury.

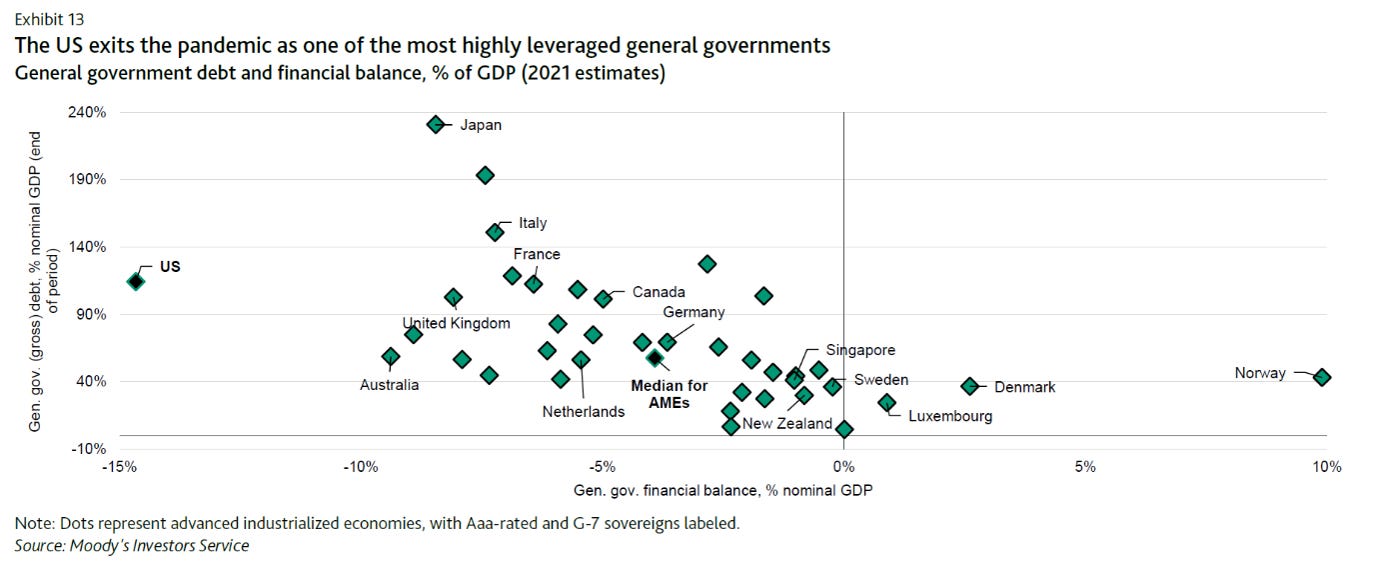

However, he does make a conceptually valid point. While Moody’s Moody’s cited rising debt and mismatched fiscal trajectories as reasons for the downgrade, I don’t think that hits the crux of the issue here. To pull an old rabbit from the hat, this is what Moody’s was looking at back in 2021. The US dwarfed its developed peers in terms of government leverage, and that picture is not too different today.

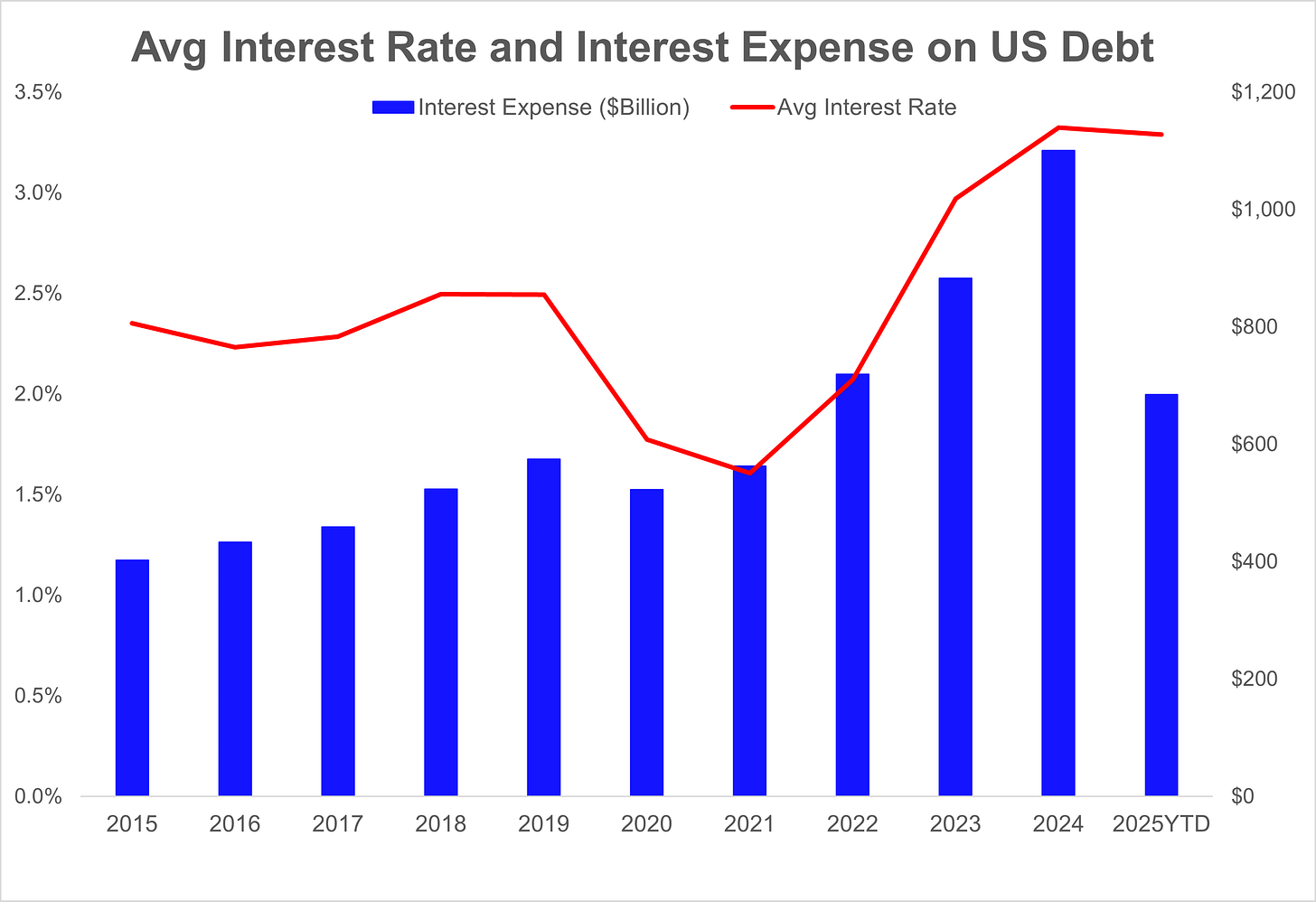

Perhaps a more worrying development since then has been the rapid rise in average interest rate on US debt and the amount the government has to fork out each year simply to repay the interest. That’s not a crisis today per se, but it’s a slow bleed that narrows fiscal space for tomorrow. If tariffs do send inflation higher and rates stay sticky, we’re looking at a structurally more expensive government.

Still, there is next to no risk of the US “defaulting” on its debt, as it can simply issue more debt, inflate away the debt, and/or print more dollars.

But the risk lies in complacency. The US government seems to operate on the assumption that it can get away with following this paradigm forever. That is to say, more than the debt sustainability issue itself, it is more worrying that there hasn’t been any genuine attempt to address debt sustainability.

Exorbitant Privilege Stems from Dollar Recycling

Don’t get me wrong — I am well aware of the US’s “exorbitant privilege”, that it seems to be able to borrow cheaply with no consequence. This privilege isn’t just about military might or economic size. It’s embedded in the global market structure.

I think about the world’s funding of the US through 2 lenses: “by choice” and “by force”.

By choice: For reserve managers, Treasuries remain the obvious pick. They're safe, liquid, and universally accepted. When you care about getting your money back more than maximizing return, U.S. debt is hard to beat.

By force: Global savings flow into Treasuries whether allocators want them or not.

Index mechanics: Most sovereign bond indices are market-cap weighted. Since the U.S. issues so much debt, it dominates the weighting.

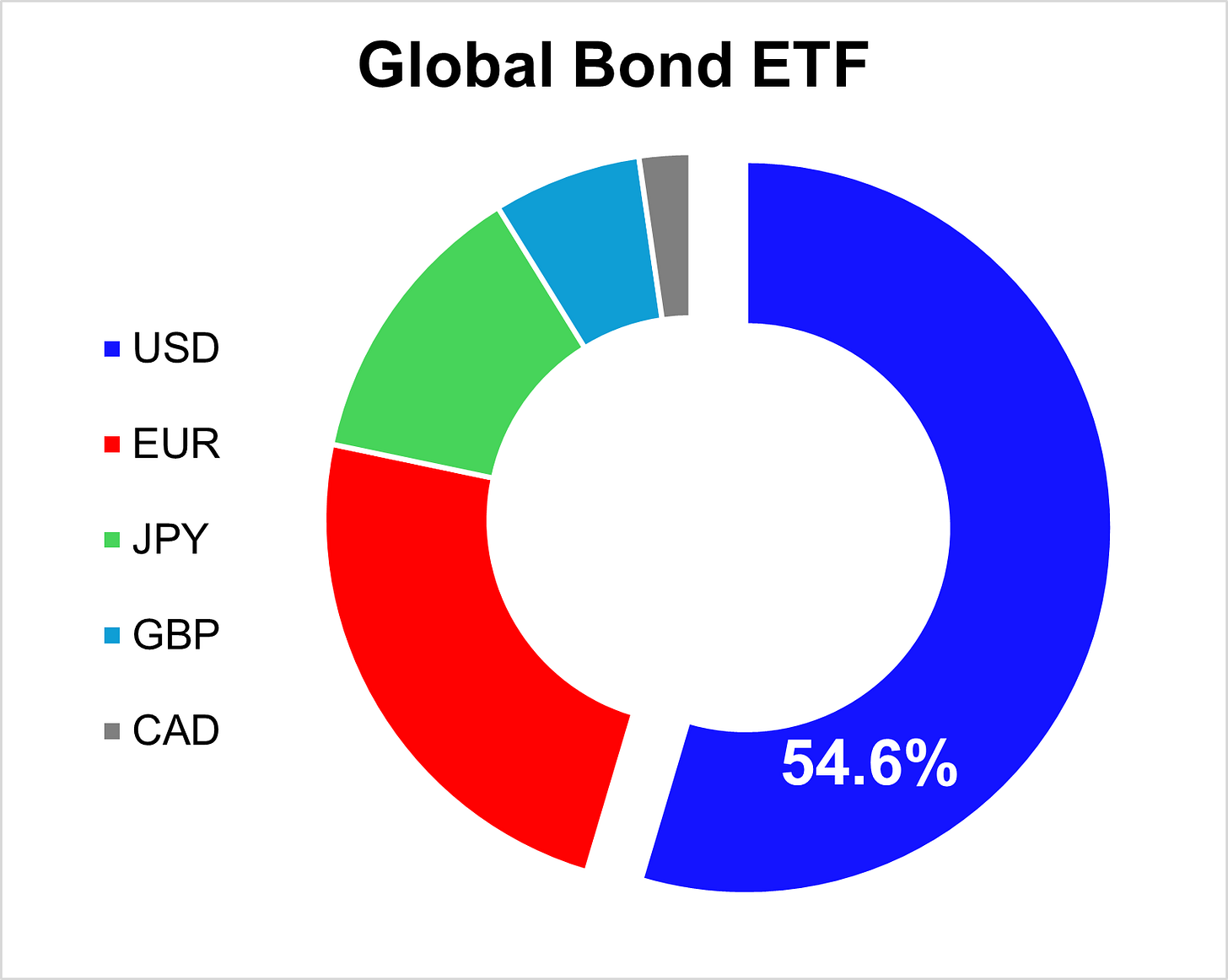

Product design: As a result, investors in “global” bond ETFs or mutual funds often end up with >50% exposure to Treasuries — not by intention, but by construction. Below is the holdings breakdown of a “global” developed government bond ETF, for example.

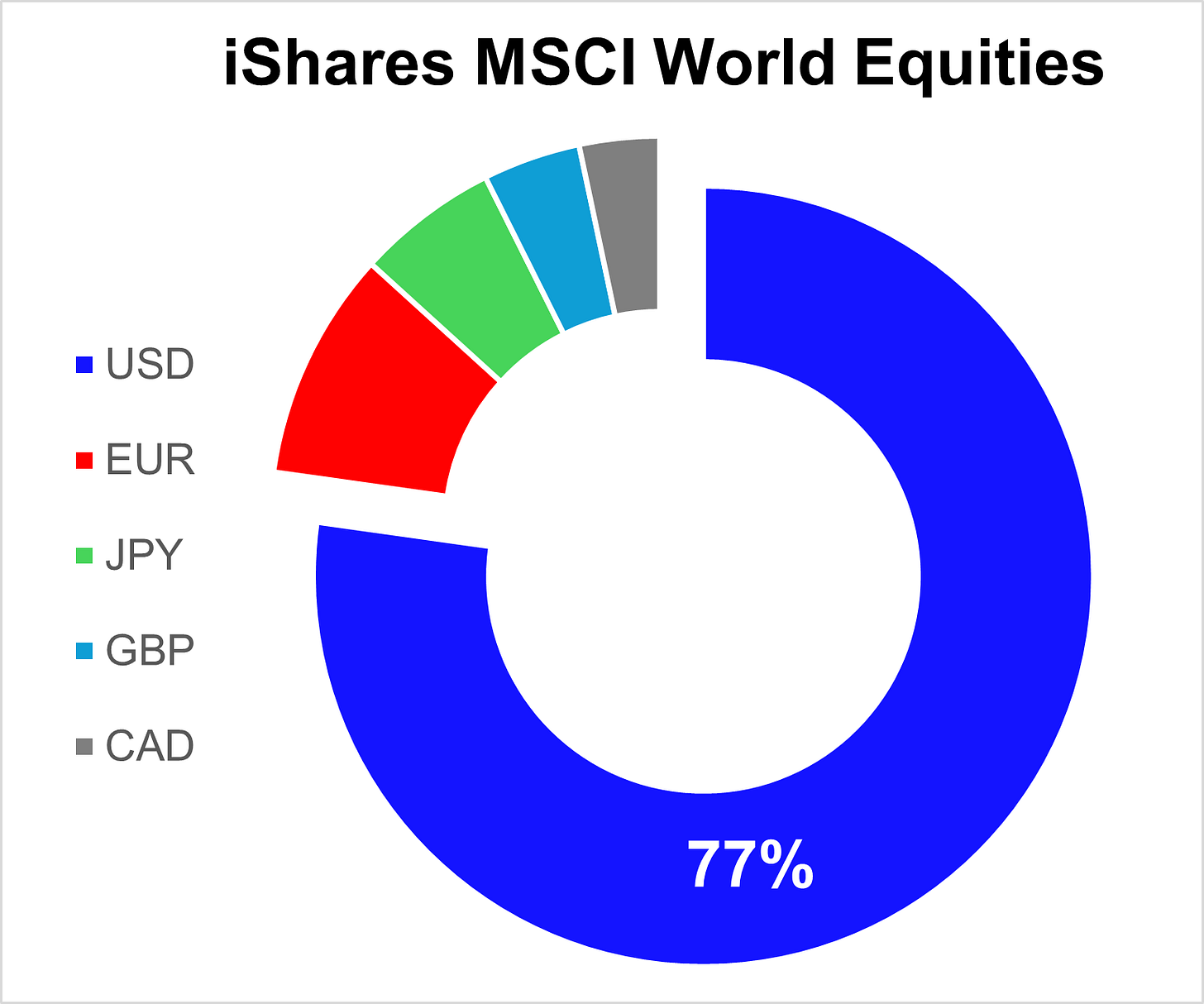

US Equities Overweighting & Portfolio matching: The world is overinvested in US equities, and perhaps for good reason. The sheer size and attractiveness of the US equities market mean that investors seeking to build 60/40 portfolios (or any other typical equity-bond portfolio) need to be equally overinvested in US debt. Say you invest in international equities in an ETF product:

You then want to construct a 60/40 portfolio by currency to manage risk/reward. This would mean that for every “diversified” share of equities product you buy, your corresponding bond portfolio needs to be 77% US bonds.

No true alternative: additionally, while other sovereigns may be “safe,” they come with quirks:

Gilts imploded in 2022.

Bunds ride the risk of Eurozone fragmentation.

JGBs offer low yields and painful convexity when rates rise.

In that context, Treasuries remain the least ugly option — by default.

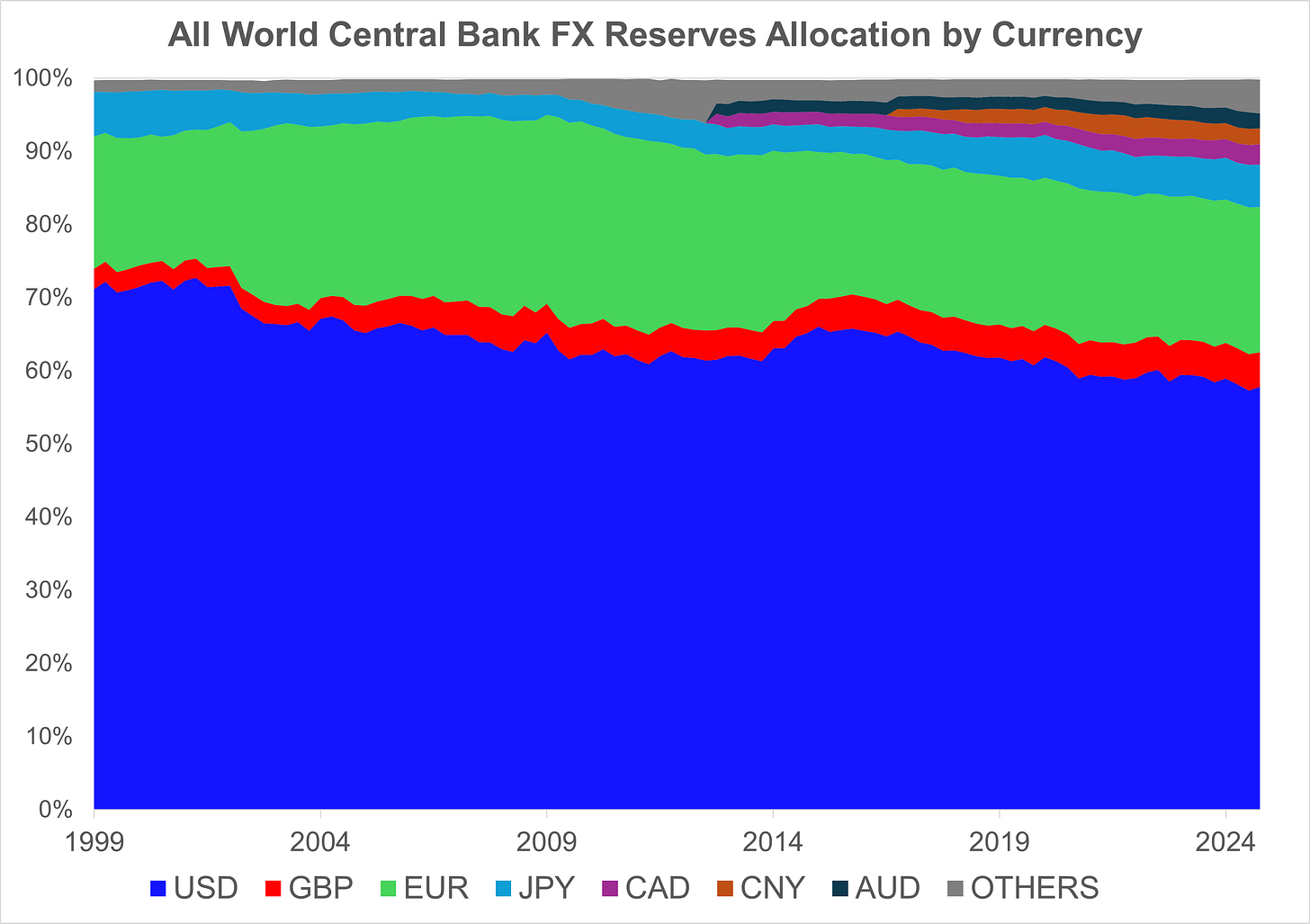

Factors above drive persistent demand for US debt — a sort of mechanical recycling of global capital back into the U.S. The charts below look at FX reserves by currency in central banks across the world. We see that for all the talks around “de-dollarization” for as long as I can remember, it has not really happened in the real world.

Volatility: The Threat Beneath the Surface

So if the structural bid for dollars is so entrenched, what could weaken it?

Volatility.

Central banks don’t panic-sell Treasuries when the U.S. runs deficits. But they do rebalance — quietly — when long-end volatility spikes.

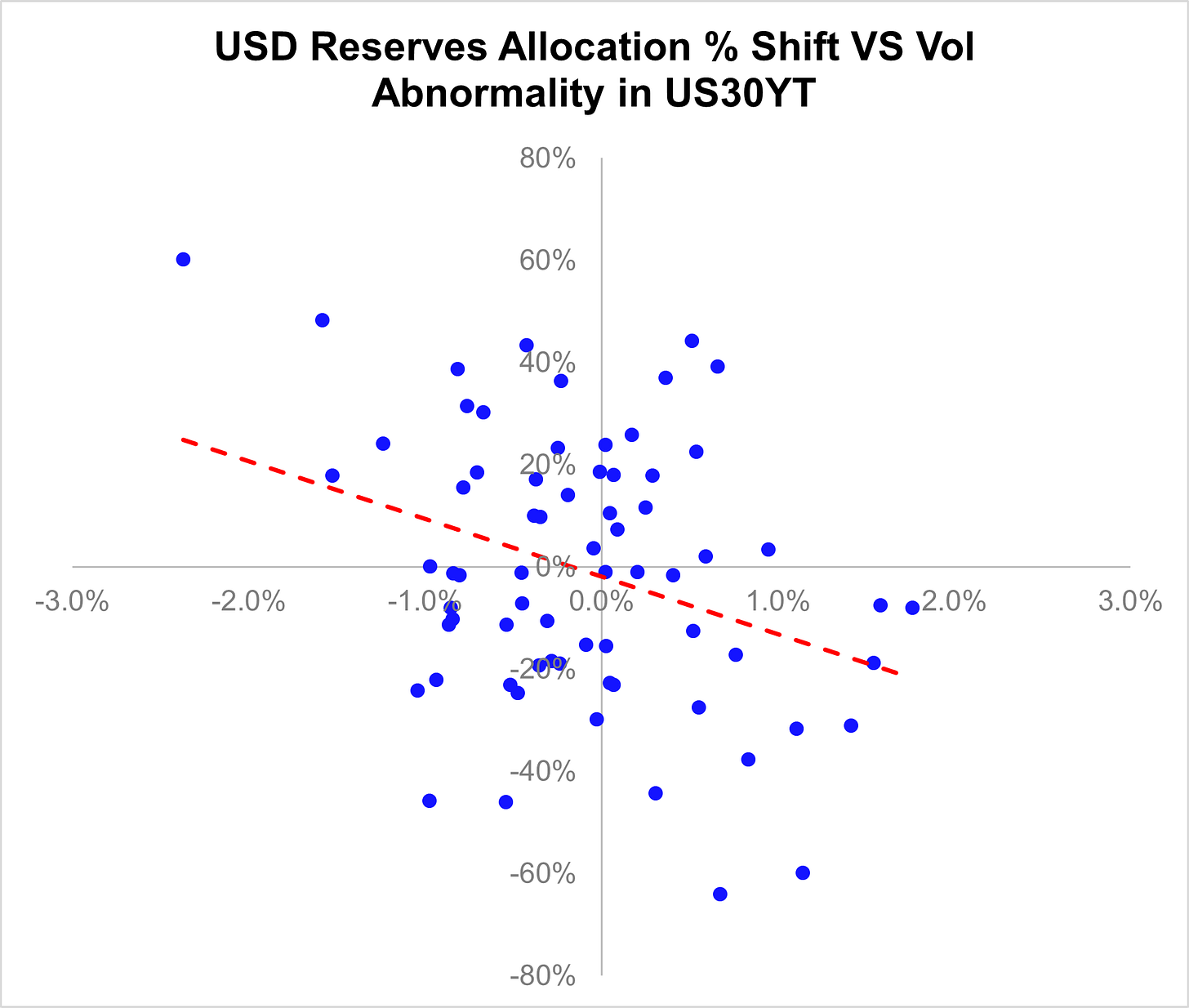

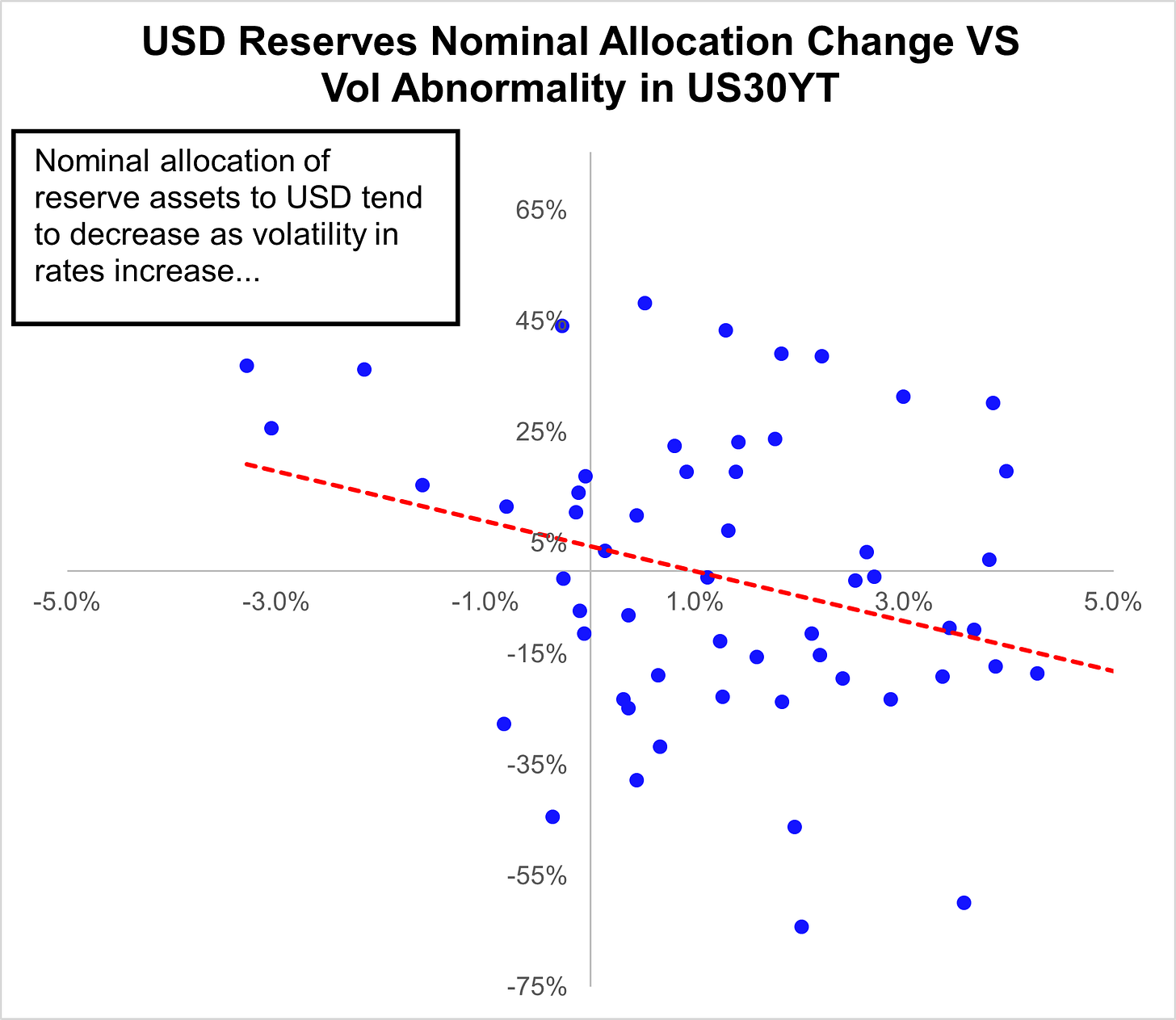

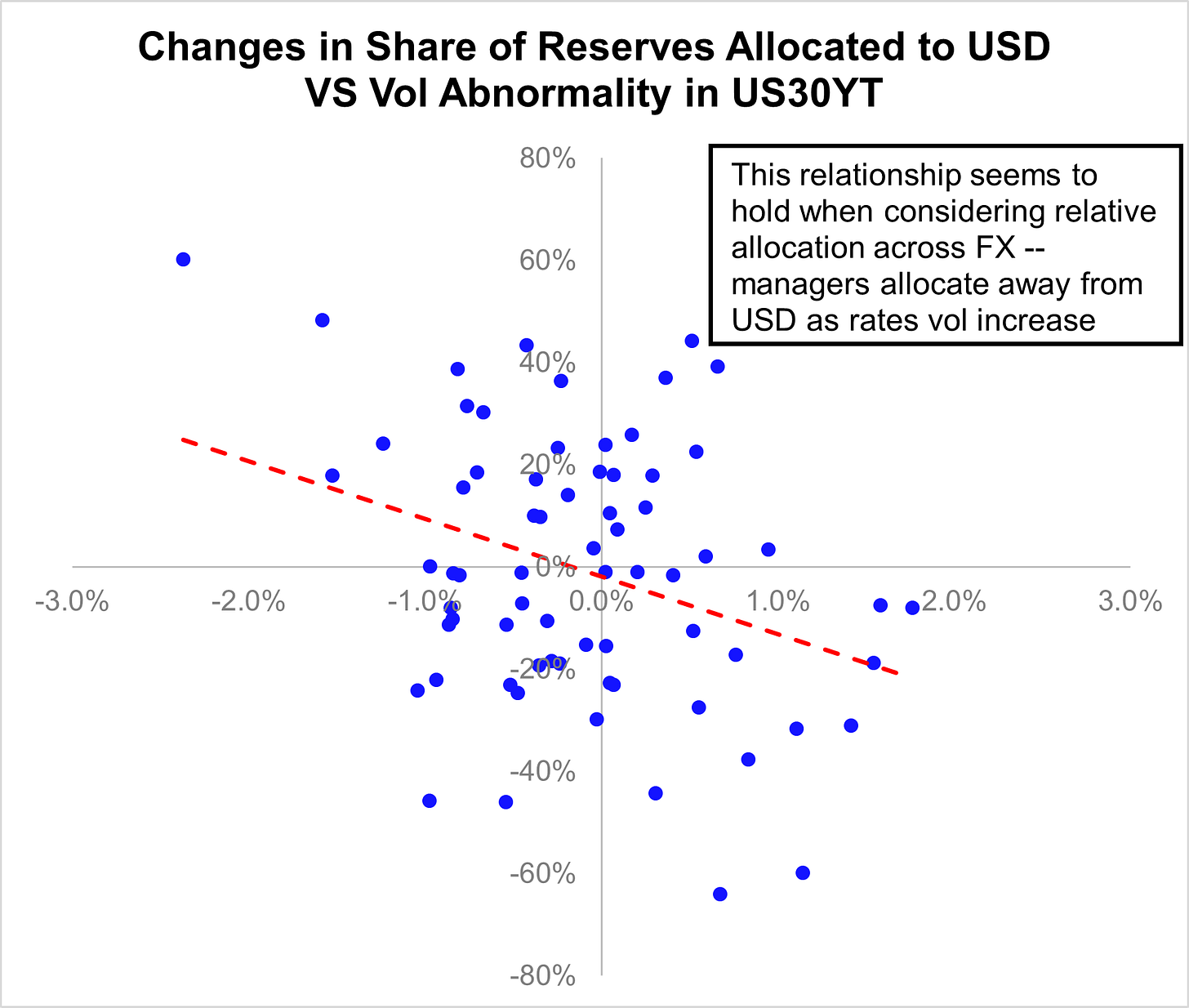

The chart below zooms in on central banks across the world, and looks at nominal allocations of reserve assets to USD against my measure of abnormality of volatility in 30-year Treasury Bonds. It points to a relationship that when vol rises, USD allocations tend to fall. It's not a crisis response, but a measured trim — the kind of marginal shift that matters when U.S. issuance is surging.

Granted, the result above is obviously not rigorous enough. Changes in nominal allocation could merely be due to valuation effect, and there is some endogeneity — these allocators can be participants in bond selloff (or rallies) themselves. I try to account for this by looking at relative allocation shares across FX, and the relationship still holds: higher preceding volatility is associated with reducing allocation away from USD and to other currencies.

The implication is simple: rate volatility, not just level, erodes the U.S.’s ability to fund itself at low cost. Not because of a stampede — but because the allocator starts to blink at the margin.

Final Thought

The U.S. isn’t facing an imminent debt crisis. But its privilege is being tested — not by letter grades, but by interest cost, market structure fatigue, and volatility risk.

If Washington continues to act as though demand for Treasuries is infinite and costless, markets may eventually prove otherwise. Not all at once — but basis point by basis point.

No investor is perfect, even if he is a robot cat with a magic pouch!

Please leave your thoughts, criticisms, and comments below to help everyone’s learning.

🐾A quick word:

Everything I share here in Robot Cat Macro is for learning, exploring, and thinking big. It's not investment advice, not a recommendation, and definitely not a shortcut to getting rich quick (trust me, if I had one, I’d have printed it out ages ago).

So before you make any big decisions, please do your own research and talk to a hooman who’s licensed to give advice. I’m just here to spark ideas — not to take responsibility if your trades go sideways.

With that said… onward, upward, and always keep a gadget handy.

– Doraemon 🐱📈

Hi